SHELTER

Directing: B

Acting: B

Writing: B-

Cinematography: B

Editing: B+

Much like Gerard Butler in his B-movie quality disaster flicks, Jason Statham has really carved out his niche in January-release action thrillers. It all started with the surprisingly fun The Beekeeper, which set the standard in 2024 thanks to its self-awareness as revenge trash, which somehow made it good. Now, last year’s A Working Man failed to meet that standard by being far too self-serious and thereby sucking out any chance of fun. (Also that one was actually released in March, but its original release date before being postponed was in January so I’ve decided it counts. Plus it still very much has that forgettable-January-action-thriller vibe. It should have been released in January.) With Shelter, we get a movie that sits kind of in the middle: it’s not as self-aware or quite as fun as The Beekeeper, but neither is it as gravely self-serious as A Working Man. It does have its comedic moments, thanks to a charming performance by a 14-year-old Bodhi Rae Breathnach. This plus Statham’s typical no-nonsense violence makes Shelter just compelling enough.

2026 is shaping up to be a banner year for early releases that are far better than anyone would reasonably expect them to be. Sam Raimi’s Send Help is the best example of this and the one film of this ilk most deserving of recommendation, but Nia DaCosta’s 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple would also qualify. Shelter is perhaps the weakest of these examples by just a slight margin, but it could also be argued that it makes the strongest case for delivering exactly what you expect of it. In any case, January and February have long been referred to as “Dumpuary” for good reason, but some filmmakers are figuring out how to make movies that fit into the genres usually reserved for this time of year but that are also actually good.

To be fair, Shelter is hardly great, but no one is expecting greatness from it, which is a key element of movies made not just simply to entertain, but to entertain simply. Statham’s previous two films featured his protagonist characters on a revenge quest, but this time director Ric Roman Waugh (who, as it happens, also directed the original Gerard Butler B-movie disaster flick Greenland) and writer Ward Parry give him a new twist this year: he’s still on a quest, but now he’s aiming to protect her from a British government that considers her a “loose end” in the framing of him as a former shadow MI6 agent.

The story and character motivations are pretty simple. Mason (Statham) has been exiled on a remote island, in hiding from a government that won’t forgive him for refusing to kill an innocent man who had worked as an informant. A man who once served with him regularly brings supplies out to him from the mainland, and has started bringing his niece, Jesse (Breathnach), along with him. And this is how Mason and Jesse meet, as she delivers the crates of supplies by rowboat from the main boat to the shore, but gets stranded on the island with him thanks to a severe rainstorm. A surprising amount of time is spent on these two alone on the island together, as Mason helps nurse Jesse’s injured ankle back to health. But when Mason is forced to take a boat to the mainland himself in order to get needed medical supplies, the British government’s far-ranging surveillance state picks him up on one of the infinite number of cameras they have access to (in this case, in the background of a TikTok video—topical!). And now, with the government alerted to his location, they descend upon the island, and this is when the action can kick into high gear.

But, does it? I’ll be fair and say there is plenty of action on Shelter, but given the kind of movie this is, I kind of wanted a little more. This movie lingers on its quiet periods a bit more than necessary. This clearly isn’t high art, so let’s just get on with what we’ve come here for. That said, a lot of the violence that does happen is pretty problematic—Shelter is wildly cavalier about collateral damage. It never seems to matter to Mason that the people he’s attacking often likely have no idea that he doesn’t really deserve what they’re attempting to do to him, and he dispatches countless numbers of them, like Star Trek “red shirts.” There is one singular villain in the hired assassin (Bally Gill) sent to kill both Mason and Jesse by the head of the shadow group Mason was once a part of (played by Bill Nighy), and we do get one moment when Mason asks him, in the middle of their climactic fight, “Do you even know why you’re doing this?” His answer: “It doesn’t matter.” Oh, he must have been reading the studio notes. This movie is less interested in providing Mason the answer to that question than in giving Mason a reason to kill everyone that gets in his way in cinematically clever ways.

I still enjoyed this movie, I want to make clear—again, it has no pretensions about what kind of movie it is. I did find it distracting how often a character would be driving a car and looking at the passenger, or at their phone, a recklessly long amount of time without looking at the road. This happens three or four times. Eyes on the road, people! I know you’re probably actually on a soundstage, but that’s no excuse.

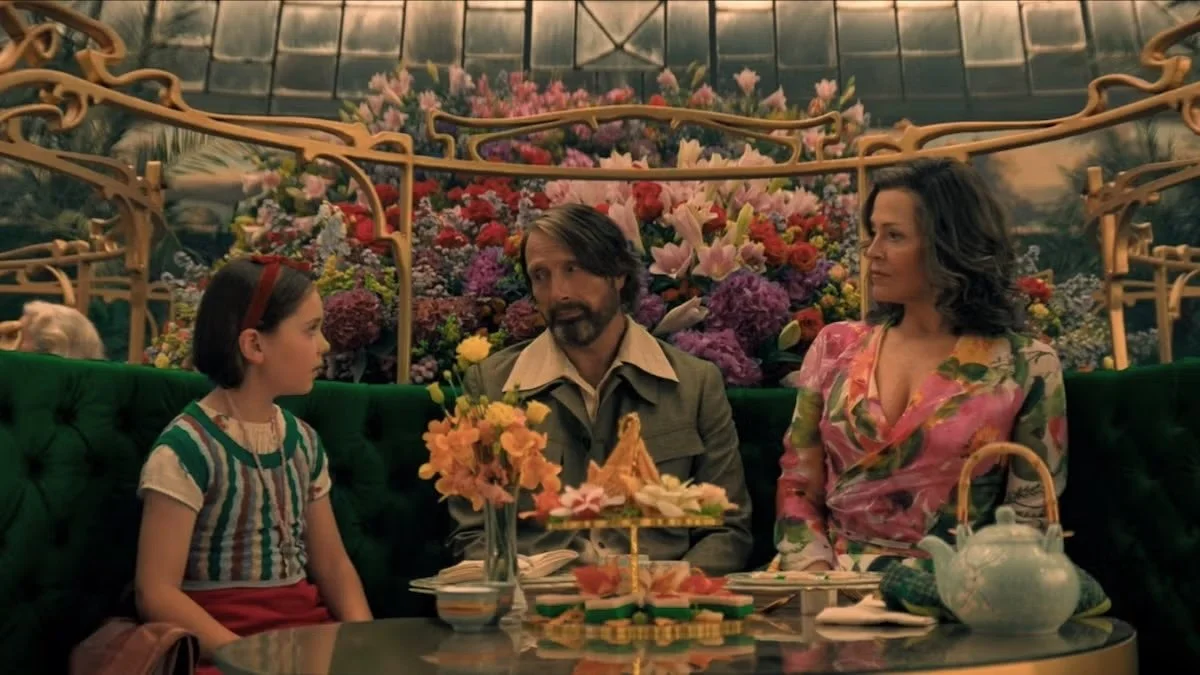

These nitpicks would make Shelter far less fun to watch if not for the solid casting of Jason Statham, who was born to play these roles in his fifties, and Bodhi Rae Breathnach, who has easy chemistry with him (she also plays the older daughter in Hamnet, proving she has versatility as a young actor). Shelter isn’t going to blow anyone away or even exceed anyone’s expectations, but it will deliver on its promise as a B-grade action thriller.

You’ll root for this odd couple in an action movie that is just fine.

Overall: B