WEST SIDE STORY

Directing: A-

Acting: B+

Writing: A-

Cinematography: B+

Editing: A-

Music: A-

When Jerome Robbins and Robert Wise’s West Side Story was released in 1961, itself an adaptation of an original 1957 Broadway play by Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim, it was a bona fide sensation. This mid-1950s musical set in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and inspired by William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, was the second-highest grossing movie of 1961 (to be fair, making less than half the gross of that year’s #1 movie, 101 Dalmatians), grossing $43.7 million—the equivalent of $406 million today. It then went on to be nominated for eleven Academy Awards, and it won ten of them.

In the context of its time, the West Side Story of sixty years ago was a perfect movie in the eyes of many—an audience of people who wouldn’t have any concept of what “brownface” even is, let alone have any issue with it. Only over time, over decades of long-established “classic movie musical” status, have people grown to understand its deeply problematic elements. This same movie that won Rita Moreno the first Oscar given to a Hispanic woman also cast white actors, notably Natalie Wood in the co-lead part of Maria, as Latin characters.

Say things like “it was a different time” all you want, watching movies like that is increasingly hard to swallow. Enter Steven Spielberg, who reportedly loved this movie since childhood, to offer the remake everyone thought no one needed, only to prove he could update it for modern audiences in nearly all the right ways. His 2021 West Side Story, which is less a remake of the 1961 film than a new adaptation of the original play—with some of the censored lines that didn’t make it into the 1961 version reinstated. (Conversely, some of the harsher lines about Puerto Rico in the “America” number are toned down a bit.)

There are some astonishing things about this version of West Side Story, not the least of which is the casting of Rita Moreno, who played Anita in 1961, as a replacement for the “Doc” drug store owner character. Here she is his widow. This is the only truly overt nod to the 1961 movie as opposed to the original play, and it’s amazing to think that Moreno was 30 years old in 1961. Consider that 1961 was sixty years ago. Just this past weekend, Moreno turned ninety. Granted, this movie that was originally supposed to be released a year ago but was postponed due to the pandemic, was shot in 2019, so onscreen Moreno is 88. Still a jaw droppingly vivacious screen presence.

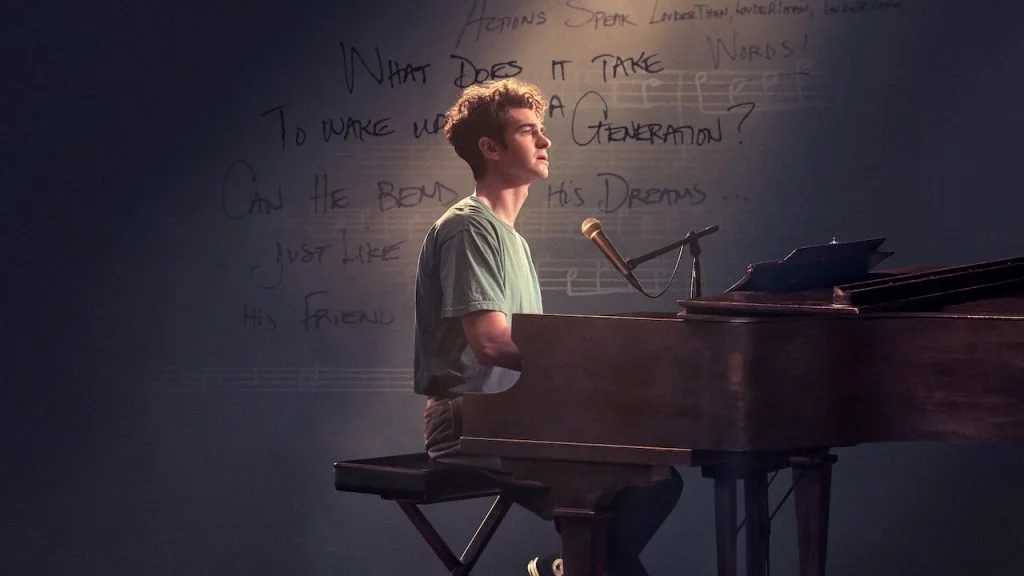

So, let’s address the issue of Ansel Elgort in the co-lead part of Tony—something that has become an unfortunate stain on the legacy of a West Side Story clearly meant to correct problematic issues. Given Elgort’s multiple credible allegations of sexual assault, that leaves this West Side Story problematic in its own right, and I must admit: this knowledge marred my experience of the movie. And I thoroughly enjoyed it! But, I was also regularly distracted by the very presence of Elgort onscreen.

Previous to this, I thought of Elgort the actor as . . . fine. He was competent but bland and forgettable in The Fault in Our Stars (2016); he was serviceable in the otherwise thrilling Baby Driver (2017)—a movie which, incidentally, costarred fellow douche Kevin Spacey. The point is, Elgort was never quite poised for movie stardom. Some may have assumed West Side Story might put him over the edge—again, he is serviceable, and his singing is actually surprisingly good—but it’s pretty clear now that is never going to happen.

It’s hard to fault the rest of the people involved in the film, however—in a highly collaborative medium. As already noted, shooting took place in 2019; the allegations broke in 2020; Elgort’s deflections have been fairly unconvincing, but this all happened after the film was done. It’s not like he could be recast. The closest I can get to putting a positive spin on this is to note that all the bronzer used in the 1961 film—even on the Latino actors!—is right there onscreen, whereas this issue with Spielberg’s film is behind the scenes. If you can’t stomach seeing this movie after learning about Ansel Elgort, I absolutely won’t fault you for that. But if you can take the film at face value, and judge it solely as Spielberg’s vision of a genuinely improved film experience, you might just find yourself wowed by it.

It should be noted that this West Side Story has an incredible ensemble cast, with Ariana DeBose every bit as good as Rita Moreno ever was in the part of Anita; a truly dynamic screen presence in David Alvarez as Bernardo; a uniquely charismatic screen presence in Mike Faist as Riff; and an essence of effortless vocal purity in Rachel Zegler as Maria.

And then there’s the part of Anybodys, portrayed as a tomboy in the 1961 film (and, presumably, in the original play), but strongly suggested—though never explicitly stated—to be a trans boy as depicted by Iris Menas in the Spielberg film. This also certainly gets into deeply sensitive territory, but, all things considered, both Spielberg and Menas handle this character incredibly well. This could have been a choice that crashed and burned, and instead the part, which gets a slightly expanded character arc (as does that of Chino, a pivotal part with no real dimension in 1961), is handled with nuance and humanity. That said, I can’t quite decide how I feel about the decision to keep the “my brother wears a dress” line in the “Gee Officer Krupke” number, except to say that it fits with the characterization of the Jets as insensitive dipshits.

Most importantly. Spielberg shoots West Side Story in a way that infuses it with crackling energy, employing cinematography that makes its viewing an invigorating experience. This is the case from the opening shot, which trades the 1961 version’s famous overhead shots of Manhattan skyscrapers with an overhead tracking crane shot of blocks of rubble recently bulldozed, immediately and pointedly contextualizing the story with gentrification. A few Black characters are used briefly at times throughout the movie, clearly in the service of this point. The story just happens to be about rival gangs that are either white or Puerto Rican.

And yes, there is still ample choreography—one of the things that made me love this movie, actually. Once enough decades passed to render West Side Story dated, some have made fun of the seemingly effeminate nature of “tough guy” gangs incorporating ballet moves into their repertoire. Well, they kind of still do that here, but Justin Peck’s choreography is updated just enough to accept the way they move as a part of a modern movie musical. Choreography isn’t just for dancing, though (although there are multiple dance numbers here that are great, especially during “America”). It’s also for fight scenes, and there are moments in this adaptation that are surprisingly violent. The opening sequences marry the two, in fact: introductions of the Jets and the Sharks have them dancing aggressively through the streets, until we wind up at a beautifully shot mural of the Puerto Rican flag, which the Jets then begin defacing with paint from cans cleverly picked up during all that previously choreographed movement.

The great thing about West Side Story is now it all fits together in the end. This is the kind of movie that pulls you along as what seems like simply decent entertainment for a while, only for things to click into place in a way that systematically reveals how expertly constructed it was all along. To say that film adaptations of stage plays, even musicals, are hit and miss is an understatement. But, how much I thoroughly enjoyed this one can’t be overstated.

Just think of it as Spielberg’s best work in years.