SIFF Advance: NOTHING COMPARES

Directing: A

Writing: A-

Cinematography: B

Editing: A

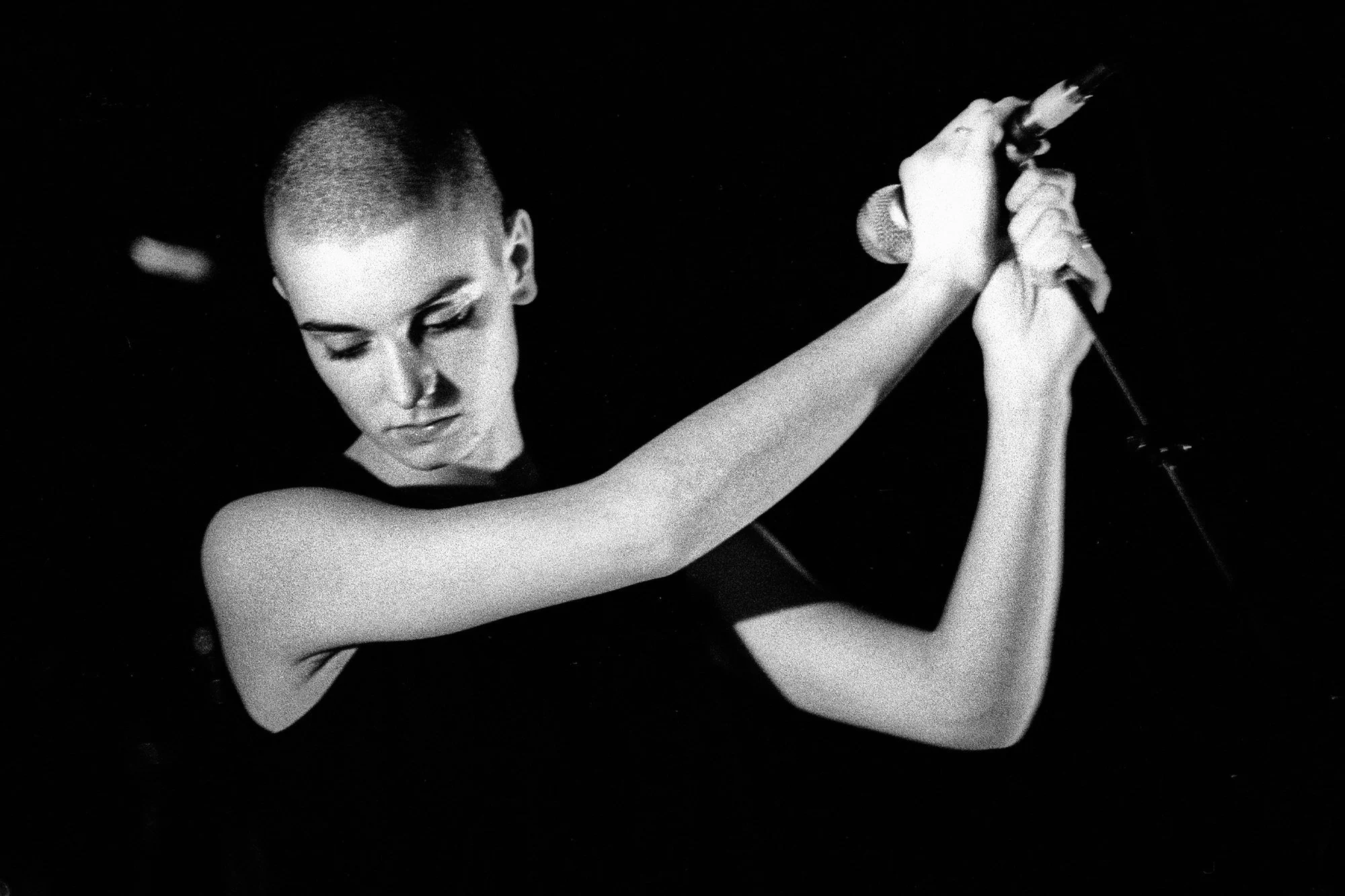

Nothing Compares begins with, and returns to again near its end, a quite notable event in Sinéad O’connor’s career that no one has really talked about since: her October 1992 appearance at the Bob Dylan 30th Anniversary Tribute concert at Madison Square Garden. She is shown coming out onstage, greeted with a stunningly equal mix of cheers and boos—because of what remains, unfortunately, the most widely known moment of her career: Two weeks before, after performing on Saturday Night Live, she tore up a picture of the Pope.

It’s been another thirty years sine that incident, and in that time, particularly in the past twenty years, the Catholic Church’s international image has been greatly tarnished and they have had much to atone for, particularly after a major 2002 Boston Globe investigation of child abuse in the Catholic Archdiocese of Boston, and an Oscar-winning 2015 film based on it (Spotlight). The massive controversy surrounding the incident notwithstanding, an incident which truly derailed O’connor’s career, it could easily be argued that these hard truths about the Catholic Church finally coming to light are thanks to the bravery of people like her.

And, as always, the people booing her at that Bob Dylan tribute concert are completely lost on the irony of their actions. Says one of the many voiceover interview subjects in the film: “People that would boo Sinead O'connor, what were they doing at a Bob Dylan concert?” This was a time, though, in which even people who thought of themselves as militant progressives still regarded religious leaders as off limits, deluding themselves into believing that they are by definition incapable of villainous behavior.

Sinéad O’connor clearly knew different. She has insisted all along that she has no regrets, and she rightfully deserves respect for that. But I still feel sad for the state of her career after 1992. Millions of people have no idea how musically prolific she remained after those first three studio albums, released between 1987 and 1992—a five-year period on which this film focuses almost exclusively. She has released another five studio albums of original material in the intervening time, with a six set to be released this year. And while I have not followed her personal life much at all, I have been keeping up with every one of these musical releases, many of which are actually quite good, not that so many who dismissed her thirty years ago would know.

I rather wish director Kathryn Ferguson would have given some focus to O’connor’s post-1992 life and career, as much of it deserves attention. She even released a 2005 reggae album called Throw Down Your Arms that is almost shockingly good, and not quite the left-field career non sequitur it seems. She had long felt an affinity for Rastafarian struggles from the start of her career, and here’s another detail no one mentions when they talk about that ripped-up Pope picture: it was done at the end of a cover performance of Bob Marley’s “War,” a song consisting almost entirely of a 1963 speech to the UN General Assembly by Ethiopian Emperor Haile Salassie, a screen on global racism. with which O’Connor drew parallels to child sex abuse within the Catholic Church.

When Nothing Compares returns to the Bob Dylan tribute concert, we learn—or are reminded—that, in the face of the ironically unruly crowd, O’connor scrapped the originally planned performance and then defiantly sang “War,” yet again. There are, of course, all kinds of arguments that could be made about the effectiveness of Sinéad O’connor’s tactics in their time, but it is impossible to watch the recording of this performance and not think of her as an extraordinary woman.

And that is what Nothing Compares does expertly, even within the limitations of focusing on only five years of O’connor’s career. It’s a little like the movie barely acknowledges the decades of output that it complains the industry and her fans ignored, but, there’s also no denying that this is the era that holds the most interest. Ferguson makes the interesting choice of never showing footage of her interview subjects; all of them, including sound bites of present-day O’connor herself, are used as voiceover with old photos and archive footage. Another unfortunate detail: because Prince was the writer who holds the copyright to O’connor’s one international #1 hit, “Nothing Compares 2 U,” and his estate refused to grant licensing, the song is never heard in this film. I kind of feel like this is fine, because it allows for some focus on her many other, just as worthy tracks.

And finally, at the very end—spoiler alert, I guess?—we finally see a relatively current Sinéad O’connor, onstage performing the closing track from her 1994 album Universal Mother (which did enjoy a bit of underground success), “Thank You For Hearing Me.” Keeping O’connor as she exists today offscreen until this moment does have a certain effectiveness. This is a woman with a well-known history of controversy and mental health issues, and it’s nice to see the moments where she is self-possessed and self-assured. These moments have long lived on performance stages, which Nothing Compares skillfully illustrates was a space safely removed from early interviews in which journalists treated her with a jaw dropping amount of condescension.

Through it all, though, Sinéad O’connor stayed true to herself in her art, and you can argue whether she was pretentious, but she never comes across as insincere or lacking integrity. That alone makes Nothing Compares worth a watch, whether you were already a fan of hers or not.

An exceptional portrait.

Overall: A-