MAESTRO

Directing: A

Acting: A+

Writing: A

Cinematography: A

Editing: A+

There’s a scene somewhere in the middle of Maestro, when Leonard Bernstein has an argument with his wife, in a large Manhattan room with the door closed. The camera remains distant, so we watch both of the characters in a wide shot, for the duration of their argument. There are no close-ups of either one of them, in the manner you would typically expect of a scene like this. It’s actually much closer to the real experience when you witness people arguing in person: you don’t get close into their personal space, and yet the tension in the room reaches you as though there were no distance at all. It’s a very unusual style of shooting, and it works perfectly, punctuated at its end by a sort of visual gag, an overture—if you’ll forgive the term—toward the heightened experience of moments like this.

It might be my favorite scene in the film, one of countless great scenes. Honestly I’m not sure I could even count the ways I loved the experience of watching Maestro. I expected to like it, and to say it exceeded my expectations would be an understatement. I’m gushing so much over it now, I fear it may make readers set their own expectations either impossibly high, or with an unfair amount of skepticism. I can only speak my truth: I loved this film.

I have said many times how seldom I like biopics that cover decades in a person’s life. It’s just not possible to distill someone’s life story within the space of two hours. Along comes Bradley Cooper, to whom I can only say: I stand corrected.

Thus, perhaps more than anything, Maestro is a triumph of editing. It begins in 1943, when Bernstein was working as an assistant conductor but had to fill in at short notice when the conductor came down with the flu; and it ends just one year before his death in 1990—which means the story spans 46 years. And yet, every single scene has much to say about Berstein and his life, and fits together to make a holistic picture of a man’s life.

Without focusing on just one moment in the man’s life, Bradley Cooper, who directed and co-wrote this film, instead focuses on Bernstein’s relationship with his wife, Felicia. More specifically, how his bisexuality affected their marriage. And the thing is, before watching this film I knew very, very little about Leonard Bernstein, but hey, wait a minute, he was queer? Well there’s the perfect doorway for me to leap right through—suddenly I’m very interested.

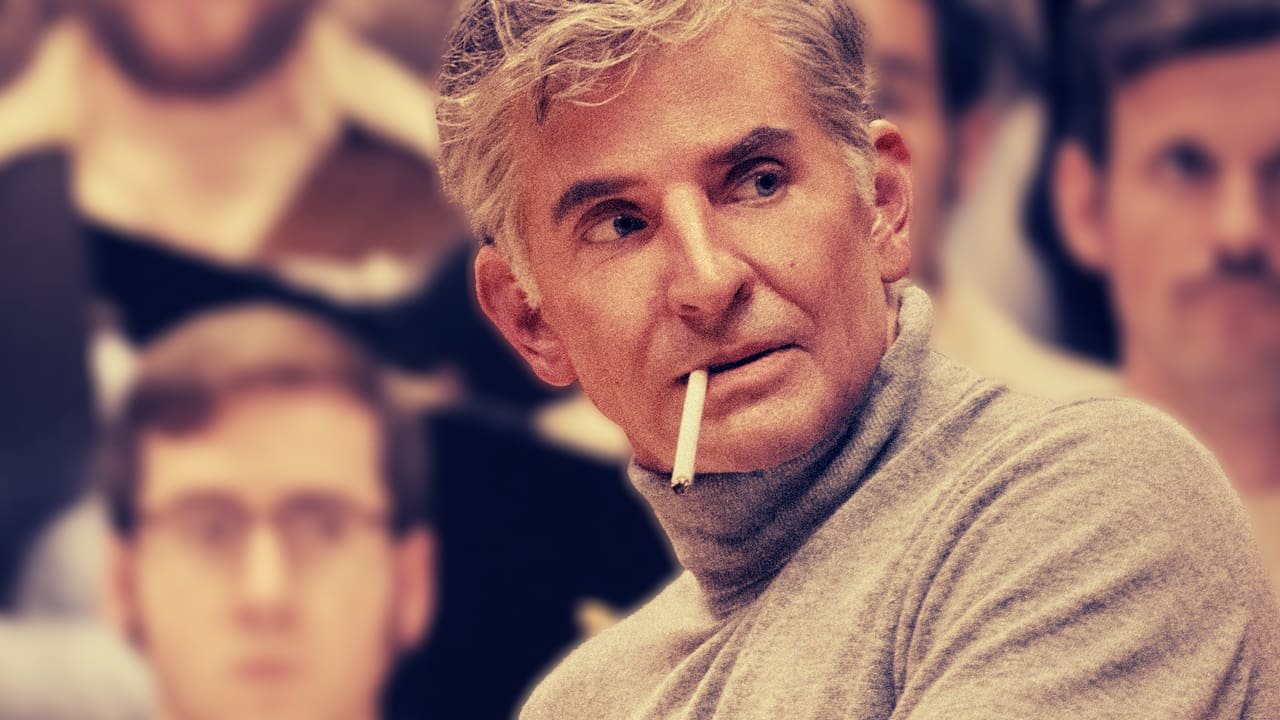

There has been a fair amount of coverage and discussion about Cooper’s decision to cast himself in this role, playing a Jewish man, wear a prosthetic nose, also playing a man who was queer. These are the things that increasingly invite crticisim: why not cast an actor who was actually both Jewish and queer? I still have no answer for that. I can only say this: Cooper’s performance is so astonishing, all of those concerns just fluttered right out of my head. I suppose it helped that he cast Matt Bomer, an openly gay actor, to play one of the objects of his affection.

Cooper is hardly new to making movies that left us wondering why we needed it, only to find it surprisingly accomplished. A Star is Born (2018) was the fourth version of that story on film, and in my opinion, turned out to be second only to the very first one, released in 1937. It also signaled to the world that, as both a director and an actor, audiences had long underestimated his abilities. Maestro goes even further, and cements Bradley Cooper as one of the great actors of his generation. I spent my time watching this film alternately marveling at Bradley’s incredibly lived-in performance, and being practically unable to believe it was really him. There’s “disappearing into a role,” and then there’s Bradley Cooper in Maestro. The fact that he did that while also directing the film is arguably the most amazing achievement I have seen in film this year.

And yet: we must not glean over the stellar Carey Mulligan as Felicia, in a performance without which Maestro would simply not work. She may not make the same kind of dramatic physical transformation as Cooper, but she stands as every bit his match onscreen. Her top billing, above even Cooper himself, is wholly justified. I have long loved Carey Mulligan as an actor, and she has never been better, in a part that in lesser hands may have been pitiful. Here, she strikes a fascinating figure, as a woman who goes into a marriage with a man whose proclivities she is perfectly aware of, and then, over time, discovers she overestimated her ability to tolerate them.

The scenes depicting the early years of Leonard Bernstein’s life and career are shot in beautiful black and white, and I think I may need to watch again to get a better sense of why the point at which it switches over to color was chosen. At the moment, I am unsure about that, and it’s the only thing about Maestro I can even come close to being critical of—except that, everything else works so well, I simply don’t care.

Maestro was edited by Michelle Tesoro, whose previous credits are mostly in television (including the spectacular limited series The Queen’s Gambit), and I am fully convinced she deserves the Oscar for Best Editing—setting aside roughly ten minutes of end credits, this film ends at an even two hours. And, with so much of a man’s life to convey, Maestro employs several unusually clever visual transitions from one scene to the next, a character walking through a doorway and suddenly they are on a new set. In every case, it’s an organic transition that propels the narrative forward, always serving the story.

Before today, perhaps the only thing I might have known or remembered about Leonard Bernstein was that he composed the music for West Side Story—as it happens, he also composed the score for On the Waterfront, for which he received his single Oscar nomination (but did not win). He’s also credited as the composer of the score for Maestro, which is indeed scored with many of his compositions. One scene even features a section of the West Side Story overture, and these musical choices are also consitently, expertly chosen.

Leonard Bernstein was the first American composer to receive international recognition, something I learned merely by virtue of watching this fantastic film. To have Bradley Cooper tell it, however, the most interesting thing about him was his marriage to Felicia, something unconventional especially for the time: they were married from 1951 until (spoiler alert!) Felicia’s death in 1978. They had three children, who don’t get prominence in this film and yet they are given appropriately vital presence, all of them in some way a reflection of the consequences of how Bernstein chose to live his life.

In the end, however, at least as far as Bradely Cooper is interested, it was about his genuine love for Felicia. I don’t have a clue how true to life the events in Maestro are, which I don’t see as especially relevant—we’re dealing with ideas and themes here, conveyed through immensely compelling characters. It does go to a very sad place toward the end, which only left me marveling at the man’s emotional—and romantic—range. Whether or not Leonard Bernstein was a good man is not really something Maestro is concerned with, which is to its benefit. He is a deeply fascinating, towering historical figure, and all we can ask for is that a biopic like this do him justice. Mileage among viewers may vary, but for me it all came together in perfect harmony.

This is actually Bradley Cooper, if you can believe it.

Overall: A