book log 2018

It's too bad when book titles don't quite make it clear what the book is about. Caitlin Doughty is a mortician YouTuber I discovered a few years back, her "Ask a Mortician" videos, which she has been doing since late 2011, being pretty consistently entertaining as well as informative. They are much more lighthearted than you might expect from something so focused on death, but that is precisely a big part of her point: death doesn't have to be dark, and Americans in particular are repressed about how they face it. ("The Good Death" in this book's subtitle is a reference to Doughty's orgaization of professionals working against death-phobic culture. Oddly, that's never made explicitly clear in this book.)

Thus, I pretty eagerly read her first book, Smoke Gets In Your Eyes & Other Lessons from the Crematory, over the summer of 2014 -- and it was one of the two favorite books I read that year. That one was much more focused on her own experiences working in the "death industry," whereas From Here to Eternity focuses outward, to the rest of the world, with each chapter focusing on a different region of the world's very different, or exotic (to us), burial customs. This does include a few outlier regions of the U.S.

This book isn't quite a good as Smoke In Your Eyes was, though it had the potential to be. With so much world travel, I would have expected at least slightly more detail than the comparatively casual way she breezes through each chapter. That said, I would still absolutely recommend this book, which is undeniably fascinating, with visits to places from Colorado to Japan to Bolivia to Tibet and plenty more. You'll learn how communing with the dead in a multitude of ways actually helps rather than hinders people's grief.

2. My Cat Yugolsavia by Pajtim Statovci (started 1/28; finished 2/7): B+

When I asked my roommate, Ivan, what book he seemed so engrossed in and he told me it was called My Cat Yugoslavia and about a gay Yugoslavian refugee in Finland who befriends a talking cat, I knew instantly I had to read it. The book, a debut by a twenty-something author who is himself a gay Kosovan emigrant to Finland (and is also pretty hot), apparently made a fair splash in Finland when first published there in 2014 (when Statovci was all of 24), and was published in the U.S. in 2017. It evidently did not have the same level of demand in the U.S., which worked well for me: it was one of the rare books I checked out of the Seattle Public Library that had fewer holds than copies, and thus allowed me to renew it before it was due back.

This was also the rare book that I finished in all of 11 days -- books can be checked out for three weeks, but I was not finished with the previous book when I first checked this one out -- a rather long time for many avid readers, sure, but for me, an unusually short amount of time. I can take weeks and weeks to finish books, even ones I am enjoying. This one kept compelling me to pick it back up.

Now. The cat in question, who is never given a name, only exists in the book for a short while: 76 pages out of a total of 255, pages 51 through 126, to be exact. I feel compelled to mention that to anyone else who might be compelled to read this book based on that description; this delightfully sadistic and sociopathic cat only exists in 30% of the story. There are other cats, elsewhere -- one which also appears to Bekim, the aforementioned gay character, in the second of three parts, but that cat is presented as a conventional, normal cat that does not talk. Another appears much later to Bekim's mother, the other of this book's two alternating narrators, which she also takes on as a pet.

I'm tempted to complain about the strangeness of this talking cat appearing without much contextual explanation, then disappearing much the same way, only to have another regular cat appear later. But something occurred to me: the talking cat is an abusive partner to Bekim as he lives in Finland, a land that abuses him as an outsider (and where, incidentally, no other character ever meets this cat); he later forges a much more egalitarian relationship with the normal cat upon a return to Kosovo as a young adult. Perhaps there are metaphors at work here? If so, the metaphors are not especially clear, but I can still work with them.

The dual narratives take place in roughly two chapters at a time, alternating between Bekim's point of view, and that of his mother, Emine, whose story first details meeting a man named Bajram whose charms quickly turn more sinister upon their wedding day. The times of each narrative move forward at different paces, until rather cleverly by the end of the book, both narrators have essentially caught up with each other and their respective stories meet in the present day. This book is the work of an unusually assured writer for his age and experience, but those things are also reflected in the plot's ultimate lack of fully satisfying cohesiveness. That said, the book is a vivid and compelling read from beginning to end, and I could not put it down.

3. The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (started 2/8; finished 3/20): B+

I read this book for one reason only: its reference in the New York Times review of My Cat Yugoslavia, which stated:

I will admit to being more than a little skeptical of this [cat] character, loyal as I am to Mikhail Bulgakov’s “The Master and Margarita” and its most iconic figure: Behemoth, that formidable hedonist against whom all fictional felines must be measured.

Oh, really? That's a pretty strong statement -- and I had never heard of this book before. I set about learning more about it. The book's Wikipedia page revealed it to be a Russian novel written in the 1930s; published first serially in Moscow Magazine in 1966-1967 and then as a book in 1967; and featuring a hog-sized demonic cat who "has a penchant for chess, vodka, pistols, and obnoxious sarcasm." Well, shit -- sign me up!

Learning that other characters included Satan himself, a naked witch, and a vampire (the latter ultimately proving just to be one of Satan's goons who happens to have one fang) were just added bonuses -- but also cemented my eagerness to bring it up to Ivan, who also loves witches and cats and, I would venture, demonic things generally -- not to mention Russia itself, thus placing it within quite a combination of his interests. I was surprised to learn he had never heard of the novel either, and I immediately put a hold on it at the library. Being both so old and non-American literature, no one else was reading it currently and I got the book very quickly.

Unlike My Cat Yugoslavia, I did take a while to finish this one, and I had to renew it once at the library: I took precisely six weeks to finish it. In my defense, this book, at 412 pages, is 157 pages longer, not even counting the 20 pages of the forward and other introductory texts, which I felt obliged to slog through. I also regularly had to page over to the 16 pages of notes in the back (why can't people stick with putting footnotes on the bottoms of pages? It's so much easier!), so I could get at least some context of the place, time and culture that would otherwise have escaped me completely; I really know nothing whatsoever about mid-twentieth-century Russian society, let alone the specificity of its literary circles, which the book apparently largely satirizes. The introductory texts did yield much information on how this book became, as the Amazon description puts it, "A literary phenomenon" -- another reason it's surprising I had never heard of it.

Curiously, much like the cat in My Cat Yugoslavia, Behemoth does not appear in this story until nearly fifty pages in either -- page 47, to be exact. His first few appearances are fleeting, however, and his presence is not very prominent until much later in the book. Still, he is indeed a fantastic character -- at one point shooting guns at people from a swinging chandelier, my favorite moment -- and easily the biggest reason to read the book.

In any case, for famous yet aging Russian literature, The Master and Margarita is quite engaging -- mostly because it is so packed with action: within three chapters a man is thrown under a tram car and decapitated, setting off a string of chaotic events perpetrated by Woland (here the name used for Satan) and "his retinue", for the vast majority of the story. Following along with rapidly growing numbers of hapless victims of this chaos goes on for so long that I began to wonder if there would be more to the story at all. What is the point of all this? About four and a half chapters switch the narrative back to Biblical times and focus on Pontius Pilate and the crucifixion of Jesus, many details embellishing or deviating from scripture -- these passages prove surprisingly interesting on their own, and they do connect to the "present day" narrative in the end. It's halfway through the novel before the two title characters even appear, let alone become even halfway clear; one chapter in the latter half of the book gets so Satanic-ritual dark that it would keep my parents up at night. Bulgakov does tie it all together in the end with impressive skill -- even if it still left me with the feeling that a hell of a lot of its now-outmoded intended satirical meanings and targets flew over my head.

4. Thanks, Obama: My Hopey, Changey White House Years by David Litt (started 3/20; finished 4/3): B+

And here my reading changed gears pretty dramatically: this is quite the light, fun, and quick read -- not least of which because there are fewer words per page. Litt's tale of working for the Obama White House does not get into the greatest of details as far as its sociopolitical implications; rather, it gets to how he went about shaping the country's perception of those things through writing -- and editing, and re-editing -- the words the president spoke. In the very beginning, I found myself thinking, Eh, this is pretty good, but it turns out this young Presidential speech writer has quite the flair for wrapping up a story. After several chapters of amusing anecdotes, Litt ends this more than worthwhile read by tying all of his experiences together with impressive finesse. His prose ends up having a surprising amount of impact with its tight polish and sincere amount of emotional heft, buoyed by reliably consistent humor.

5. The Ten, Make That Nine, Habits of Very Organized People. Make That Ten: The Tweets of Steve Martin by Steve Martin (started 4/5; finished 4/6): B-

To call this one "light reading" would truly be an understatement, as it's a collection of amusing tweets by Steve Martin from 2012, barely 100 pages long. The book itself is small in size, almost like a pamphlet, and six years on, to be perfectly honest, the novelty has much dissipated. Don't get me wrong -- Martin is on brand here with his typically absurdist humor and I laughed out loud relatively consistently. That said, in the long run, this will likely prove to have been Steve Martin's most quickly dated "literary" work. At the very least, with only between one and maybe five tweets per page, all of them limited to 140 characters (it would be another five years before Twitter doubled that limit), I can say I finished one book this year in two days.

6. All We Can Do Is Wait by Richard Lawson (started 4/6; finished 5/4): B

I only know about this young adult fiction novel because I follow Vanity Fair entertainment writer Richard Lawson on Twitter, which I started doing after hearing him co-host the awards season podcast Little Gold Men with Joanna Robinson, who herself co-hosted the Game of Thrones podcast A Cast of Kings. So, a fair amount of degrees of separation led me to him, but I enjoy him, and thought the concept -- teens meet each other in the waiting room of an ER to get news of loved ones after the collapse of a Boston bridge -- sounded interesting. And it is; in fact the book is not nearly as much of a downer as the concept might suggest. It's not exactly classic literature, but it has its moving moments, especially between a gay boy and his sister who was his boyfriend's best friend.

7. Calypso by David Sedaris [audiobook] (started 6/11; finished 7/11): B+

The thing with David Sedaris is, he tends to range from really good to great. Calypso, his latest collection of essays -- following on the heels of last year's fantastic Theft by Finding: Diaries 1977-2002 -- falls on the "really good" side. I do suspect I may have enjoyed it even more had I read the book rather than listened to it; I'm the truly rare David Sedaris fan who did not fall in love with him first by hearing his distinctive voice on the radio, but rather by reading his great 2000 collection Me Talk Pretty One Day in bound book form before I even knew who he was. As such, I prefer reading his works to listening, although the latter is fine -- and in this case, I got it as an audiobook as a free sample from Audible so I'd have something to listen to as my husband and I drove from the Idaho Panhandle to Yellowstone National Park in June. Unfortunately, Shobhit asked me to stop playing it because, even though he clearly could appreciate the value of Sedaris's unparalelled prose, the soothing voice was putting him to sleep. I ultimately finished this listening it in fits and starts while at work, and reading other books concurrently at home. And although he seems to be getting slightly more crotchety in his older years -- particularly in how he relates to his poor longtime boyfriend, Hugh -- this essay collection is just about as well worth the time as any of his others. Some of it gets a little bittersweet as he ruminates on his complicated relationships with a long-since passed alcoholic mother and a very old, FOX News-watching conservative father, but the more poignant ones are arguably the better pieces.

8. The Power by Naomi Alderman (started 7/28; finished 8/7): B+

For me, this is basically this year's Parable of the Sower: I love me some feminist dystopian fiction recommended by Laney! Also, comparing this to Margaret Atwood (author of The Handmaid's Tale) would be the opposite of a stretch, given that Atwood gets the first thanks in Alderman's acknowledgments.

All that said, The Power, about the shifting global dynamics after an electric power awakens in women that gives them greater strength than men, clearly wants to have the literary endurance of The Handmaid's Tale, but will never have it. It's absolutely worth reading, and I will recommend it far and wide, but it is also not a classic. Its laudable thematic ambitions, effectively unsettling though they are, buckle slightly under the weight of its writing style choices, including a fair amount of dialogue that fails to ring true.

Then again, I could not put this book down, and for me that's a rare thing indeed. And to say it offers truly provocative food for thought is truly an understatement: no man could have written this and have it come across the same way. This takes the notion that women are just as corruptible as men, but just aren't in the same numbers because they don't have the power, to its logical extreme.

9. My Life as a Goddess: A Memoir Through (Un)Popular Culture by Guy Branum (started 8/7; finished 8/28): A-

As with many things since early 2016, I first became aware of Guy Branum through the podcast My Favorite Murder -- he was the first of very few guests they have ever had on, to provide certain legal insights on their true crime obsessions, on their 49th episode at the end of 2016. He started popping up on other podcasts I listen to, and then I began following him on Twitter, bringing us to the marketing extravaganza for this comic memoir he put out this year.

I must admit: while My Life as a Goddess was compelling from the start, I was at first disappointed by the striking low number of laughs in the first chapter or two of the book. But, good things come to those who wait, and this book proves to be an expertly structured narrative about the self-actualization of this tall, fat, bald gay guy from a Northern California farm town who ultimately wound up with sweet writing gigs on shows like Chelsea Lately, Billy on the Street and The Mindy Project. The laughs come in steadily increasing frequency, often in delightfully surprising ways, making them feel earned in a way not often found in memoirs by comics. Because this isn't just comedy -- it's a tightly polished tale with underpinnings of gravitas. In the end, that made it my favorite of the books I read this year thus far.

10. I'll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman's Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer by Michelle McNamara (started 5/18; finished 9/18): B+

This book has a unique cultural context, both broadly and specifically as it pertains to me. For me as a fan, I came to it from two different avenues which sort of met in the middle. Michelle McNamara first became known to me only as the wife of one of my favorite comedians, Patton Oswalt. I knew nothing of her longtime obsession with the Golden State Killer, or her widely respected True Crime Diary podcast, or her many true crime articles published in mainstream newspapers and magazines -- let alone how well-trusted she was among a wide swath of law enforcement working with her as she did her extensive research. I simply learned who she was when she died suddenly in her sleep at the age of 46 in April 2016, and was incredibly sad for Patton and their young daughter. Conversely, I had just started listening to the then-new podcast My Favorite Murder at that time, and although I wasn't especially a true crime fan like they are and never have been, I got into that podcast due to my discovery of the wonderful and hilarious Karen Kilgariff on a different podcast, Do You Need a Ride? I've been a huge fan of them ever since, and, no surprise, a) Karen Kilgariff is of course friendly with Patton Oswalt; and b) she and co-host Georgia Hardstark talked extensively about the exciting news that Patton was assisting in finishing the book Michelle had been in the middle of writing at the time of her death, and getting it published. So then, with the addition of a forward by crime novelist Gillian Flynn; a brief, third section written up by journalist Billy Jensen and researcher Paul Haynes; and an afterward by Patton himself, the book was published in February of this year.

And: it is very good -- as had already been asserted by Patton, Karen, Georgia and a slew of their colleagues I also follow on Twitter. The 3/4 of it written by McNamara herself is superb, especially the six-page "Letter to an Old Man" that closes it all at the very end, addressing the Golden State Killer and detailing the inevitable when technology will finally catch up with him. (Stunningly, suspect Joseph Deangelo was identified via DNA match, and he was arrested less than two months after the book's release -- a spectacular day for his victims, for Patton Oswalt, and for Michelle McNamara's legion of fans.) Were McNamara able to finish the entire book, I'm sure the entire thing would have been superb -- it is impressive in its earliest pages how she demonstrated intricately detailed knowledge of seemingly infinite amounts of evidence, all the suspects, and all the victims. She also took care in a way I'm not certain a male author would have, of focusing on the attacker's techniques of approach and escape, and never dwelling on the specifics of the attacks themselves. Very occasionally, she would throw in a truly disturbing detail in passing, just to underscore how very sophisticated were his methods of terrorizing. And it's not to say the rest of the book, with other writers tying up McNamara's loose ends as best they could (before they had any idea the man would be caught so soon after publishing), is at all sub-par. It's just in a different voice, giving it a vaguely disjointed narrative effect.

When it's McNamara's voice, it's unparalleled. I will admit to taking quite a long time to read this book -- as you can plainly see by my start and end dates. It was a couple of weeks overdue when I first had to return it, being unable to renew thanks to the hundreds of holds at the library upon its first release. I was all of 72 pages in, had to return the book, and read three other books in the meantime. The book's popularity evidently fell off a cliff, perhaps partly due to a wealth of information now available on the killer that McNamara was not privy to, and when I renewed it this last time, I was able to because there were suddenly only about 20 holds on the library's 154 copies. But I assure you: this book is still well worth reading, on the strength of Michelle McNamara's investigative skill and narrative prowess alone.

11. Everybody Lies: Big Data, New Data, and What the Internet Can Tell Us About Who We Really Are by Seth Stephens-Davidowitz (started 9/21; finished 10/10): B+

This book is so thoroughly researched that although it's listed as being 357 pages long, it actually ends on about page 285 -- before the extensive acknowledgments, notes, and index. And Stephens-Davidowitz contextualizes "Big Data" in a way that has arguably never been done for mainstream audiences before, giving solid evidence for how it can be used with an effectiveness no previous form of research ever could (fun fact! based on millions of Google and porn searches, we can pretty much accept that 5% of men are gay, or have same-sex attraction), as well as how it can't be used (spoiler alert! any dreams of using Big Data to get rich off the stock market should be put to bed right now). Given the striking disparity between how people self-report to pollsters and surveys, and how their true selves are revealed by online and digitized activity, this book presented example after example that flew in the face of conventional wisdoms we all take for granted. This research even illuminates how people lie to themselves, and had me wondering how much of my own thinking has been misguided. I love all sorts of statistical analysis, so this book was really up my alley.

12. Vancouver Special by Charles Demers (started 10/11; finished 11/1): B-

I have a feeling Vancouver Special would have worked better for me had I read it upon its first publication in 2009. I almost certainly would have given it a better grade at the time. But, much is made by Demers of the dual impact on the city of Vancouver, B.C., of what had already occurred with Expo 86, and what was expected of the then-imminent 2010 Winter Olympics. Nearly a decade later, there's just no escaping the fact that this book is now a bit dated. Furthermore, given that Vancouver is my second-favorite city on the globe (alas, I realized only relatively recently, whatever might wipe my favorite city, Seattle, off the map -- nuclear annihilation, meteor -- is just as likely to decimate Vancouver), I kind of wanted this book to be . . . better. I only learned of it from Demers's Oct. 8 appearance on the WTF with Marc Maron podcast, and, knowing that he is a Vancouverite comedian, I thought this book might have a bit more humor than the tiny sprinkling it has. Most chapters have some quote from a local comedian about the neighborhood or group of people the chapter is about, but even those are only moderately funny at best. The semi-problematic thing I saw about this book was Demers's vague smugness as a third-generation Vancouverite, a "native" with two grandparents (one on each side) who were also born there, clearly regarding himself as "learned" regarding all the groups his essays focus on in turn: "Black History" is three pages mildly defensive about the perception that Vancouver has no black residents, then notes the population is 1.2% black; "First Nations" is relatively detailed about colonialist history but still very much from the perspective of a straight white guy (however many bona fides having a gay brother and a gay dad he might think gives him); moving on from minority populations to other groups like "Rich People" and "Vanarchists" still in their own way illustrate the sense of something missing here: that is, the true perspective of those people he's writing about. I would love an updated version of a book like this, where it included perhaps pointed yet still friendly responses written by a local black person, or first nation person, or hell, even rich person -- he writes about one really rich friend, after all. Vancouver Special (the title a colloquial reference to a local form of housing architecture) did offer insights into a city I have long loved, that being the reason I'm not sorry I read it, but stops short of offering either the depth or the humor it seems to promise. I would have been happier with even just one of those things.

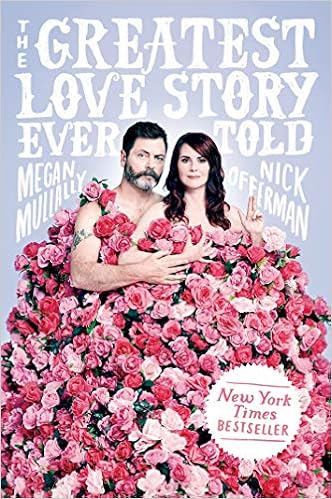

13. The Greatest Love Story Ever Told by Megan Mullally and Nick Offerman (started 11/29; finished 12/30): B

Okay, full disclosure! I haven't exactly finished this book yet. But I'm almost done! It's over a week overdue already and I'm going to get it done by New Year's Eve! And? ...And, well, okay it's an amusing enough autobiographical account of a couple B-list celebrities and how their unique relationship has lasted nearly two decades. The hyperbole of the title is obviously part of the joke, because, yes, there have been greater love stories told. This one isn't so bad though. I got a few good chuckles out of it.

[posted 7:32 a.m.]